Why GPUs? And Why DG?

Introduction

Modern high-performance computing is transitioning to be heavily reliant on GPU accelerators to achieve peak performance FLOPs. For example, Sierra at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has a peak total of 125,626 TFLOPs and 120,960 peak TFLOPs are performed by the NVidia V100 GPUs. So we can see that about 96% of the total FLOPs are done by the GPUs.

Figure 1 - Sierra Supercomputer at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Source.

In this transition, we have to look to methods that meet the constraints set forth by the GPUs such as small memory (i.e. NVidia Tesla V100 has 16 GB of memory) and perform optimally when there exists a high arithmetic intensity. We define high arithmetic intensity as the ratio of FLOPs per byte of memory. Therefore we need to look into methods that perform as many computations for every byte of memory that we transfer to the device. On the more physics side of scientific computing, there is also need for higher order methods to help reduce the numerical diffusiveness. To summarize, here are the three criteria for choosing an algorithm to help us transition into modern high-performance computing:

- Low memory footprint

- High arithmetic intensity

- High order method

Figure 2 - NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU. Source.

Finding an Appropriate Method for GPUs

The classical finite difference (FD) method offers a great and simple spatial discetization for PDEs but the stencil size grows as the order of the method increases. Moreover, FD method has difficulty with shocks due to solution of the strong form equations. Although [1], provides modern point of view on the finite difference method. The finite volume (FV) method offers an alternative where the weak form of the equations are considered and thus the differentiation requirement of the solution is dropped. However, FV method also suffers from the increasing stencil size as the order of the method increases. In [2], Shu provides a helpful discussion in the differences of FD, FV, and discontinuous Galerkin (DG) method. Loffeld and Hittinger discuss the arithmetic intensity of the FV method for 3rd through 8th order in [3].

Nodal discontinuous Galerkin methods offer a good solution to our criteria of high arithmetic intensity and high order methods. With DG methods, it is very easy to increase the order of the method to achieve high orders. One of the good characteristics of DG methods is that the stencil remains within a single element and its adjacent elements providing a great way to scale parallelization. However, we should note that in order to fulfill the high arithmetic intensity we should consider nodal DG in the matrix-free setting. Since DG discretization operator can be formed from small dense matrices then we can expect the arithmetic intensity to be high. The Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory provides this nice figure for arithmetic intensity and some popular methods:

Figure 3 - Arithmetic intensity for popular methods. Source.

Although nodal DG offers a viable option for modern high-performance computing, DG methods paired with explicit time integration methods suffer from severe time step limitations as the order increases according to [4]. Timestep approximately scales $\Delta t \lesssim C h /p^2$, where $h$ is the element width, $p$ is the order, and $C$ is the Courant constant, for hyperbolic systems. Therefore, it is convenient to use implicit time integration schemes to sidestep this restriction. The switch to implicit then implies that for each time step we need to solve a linear system to find the updated solution. Solving a sparse linear system is usually done through some Krylov subspace method and we usually need to precondition. [5] provides a great resource for solving sparse linear systems.

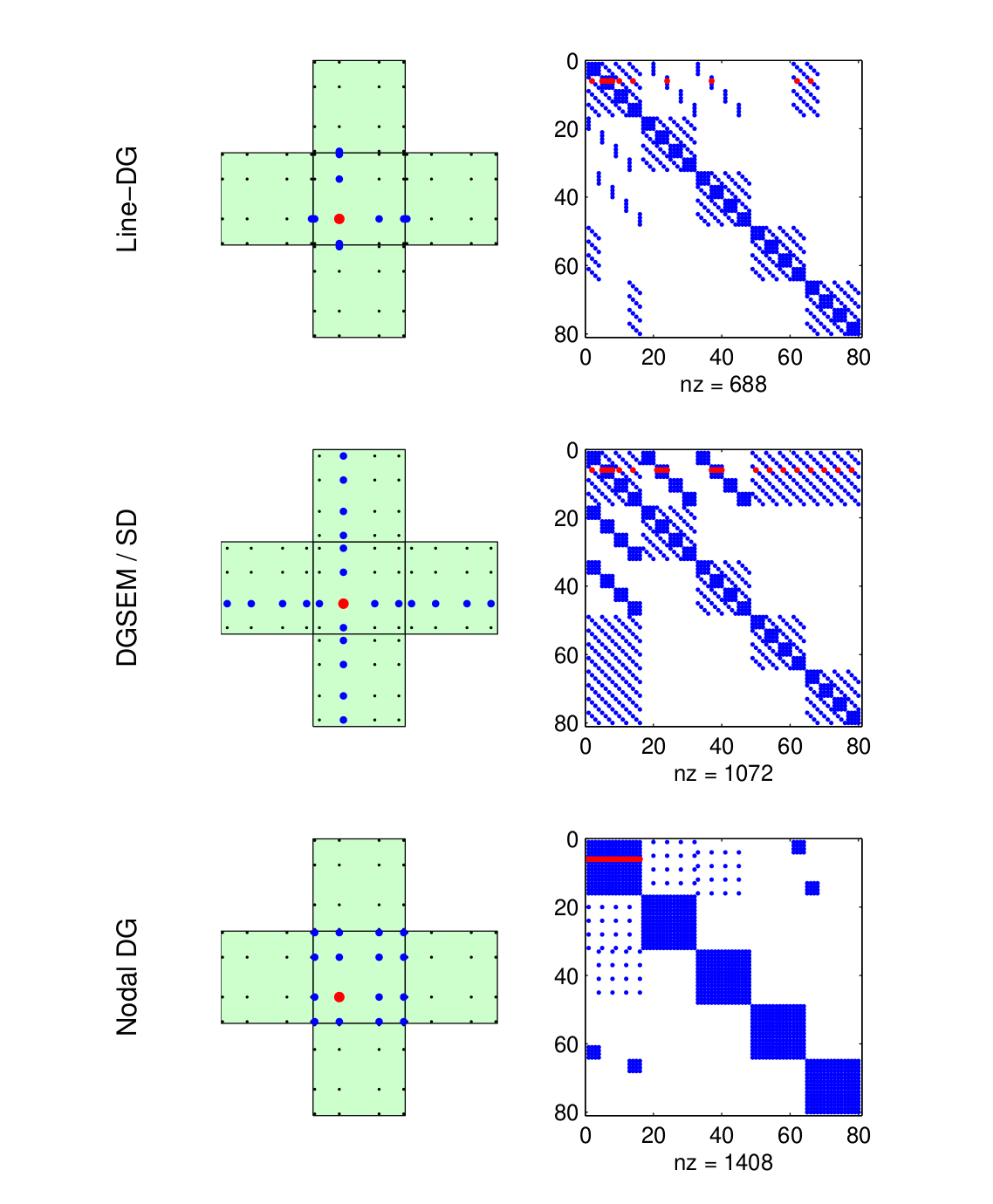

In order to precondition, then we usually need to form the Jacobian matrix. Although the Jacobian matrix might be sparse, it might still end up being quite large for the memory size restrictions that GPUs present. For this reason then we need to look for a way to reduce the memory footprint of Jacobian matrix of the nodal DG method. In this case we look to using the line-based discontinuous Galerkin (line DG) method presented in [6]. We should note that this method only considers tensor-product elements and any discussion going forward will be strictly about such elements. The goal of line DG is to provide a sparse spatial discretization. In the following figure taken from [6] shows the stencil and sparsity patterns of nodal DG, DG-spectral element method (DG-SEM), and line DG for a 5 element 2D mesh. One of the important things to note the how much sparser the main diagonal blocks are for line DG vs. nodal DG.

Figure 4 - Stencil and sparsity pattern of a first order operator for line DG, DG-SEM, and nodal DG Jacobian matrix. The blue points show the connectivities to the red node under consideration. Source

Figure 4 - Stencil and sparsity pattern of a first order operator for line DG, DG-SEM, and nodal DG Jacobian matrix. The blue points show the connectivities to the red node under consideration. Source

Conclusion

Looking back our initial goals then we have concluded that a matrix-free DG method will be best choice to satisfy our goal for high arithmetic intensity as well as a high order method. However, nodal DG’s memory footprint was too large and thus we needed to look for a sparser representation which led us to line DG. However, one issue that arises with impicit time integration is the need to precondition and most techniques rely on the construction of the Jacobian matrix which won’t be necessasirily possible if we are in the matrix-free setting.

References

[1] Reyes, Adam, et al. “A variable high-order shock-capturing finite difference method with GP-WENO.” Journal of Computational Physics 381 (2019): 189-217.

[2] Shu, Chi-Wang. “High order WENO and DG methods for time-dependent convection-dominated PDEs: A brief survey of several recent developments.” Journal of Computational Physics 316 (2016): 598-613.

[3] Loffeld, John, and J. A. F. Hittinger. “On the arithmetic intensity of high-order finite-volume discretizations for hyperbolic systems of conservation laws.” The International Journal of High Performance Computing Applications 33.1 (2019): 25-52.

[4] Krivodonova, Lilia, and Ruibin Qin. “An analysis of the spectrum of the discontinuous Galerkin method.” Applied Numerical Mathematics 64 (2013): 1-18.

[5] Saad, Yousef. Iterative methods for sparse linear systems. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2003.

[6] Persson, Per-Olof. “A sparse and high-order accurate line-based discontinuous Galerkin method for unstructured meshes.” Journal of Computational Physics 233 (2013): 414-429.